The Judiciary Act of 1802

I'm not a lawyer, but I did stay at a Holiday Inn Express last week and I think this Act might be the basis for President Trump cleaning up the radical District Courts.

Thomas Jefferson’s presidency marked a pivotal shift in the dynamics of American governance, particularly in his efforts to reshape the federal judiciary, his situation was very similar to that faced by the Trump Administration.

One of his administration’s notable legislative achievements was the Judiciary Act of 1802, which repealed the Judiciary Act of 1801 and significantly reduced the number of federal courts. This act was not merely an administrative adjustment but a calculated political move to undo the Federalist expansion of judicial power under John Adams, reflecting Jefferson’s broader vision of limited federal authority and his distrust of an overreaching judiciary. By examining the context, provisions, and consequences of the Judiciary Act of 1802, we can understand how Jefferson achieved these reductions and the lasting impact on the American judicial system.

The Judiciary Act of 1801, passed in the waning days of Adams’ presidency, was a Federalist attempt to entrench their influence in the judiciary as they lost control of the executive and legislative branches to Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans. This “Midnight Judges Act” expanded the federal court system by creating sixteen new circuit court judgeships and reducing the number of Supreme Court justices from six to five (effective upon the next vacancy), thereby limiting Jefferson’s ability to appoint a justice early in his term. It also relieved Supreme Court justices of the burdensome duty of “riding circuit” - traveling to preside over circuit courts - by establishing a new tier of circuit judges. Federalists filled these new positions with loyalists, many appointed in the final hours of Adams’ administration, earning them the moniker “midnight judges.” To Jefferson and his party, this was an egregious overreach, bloating the judiciary with partisan appointees and threatening the balance of power.

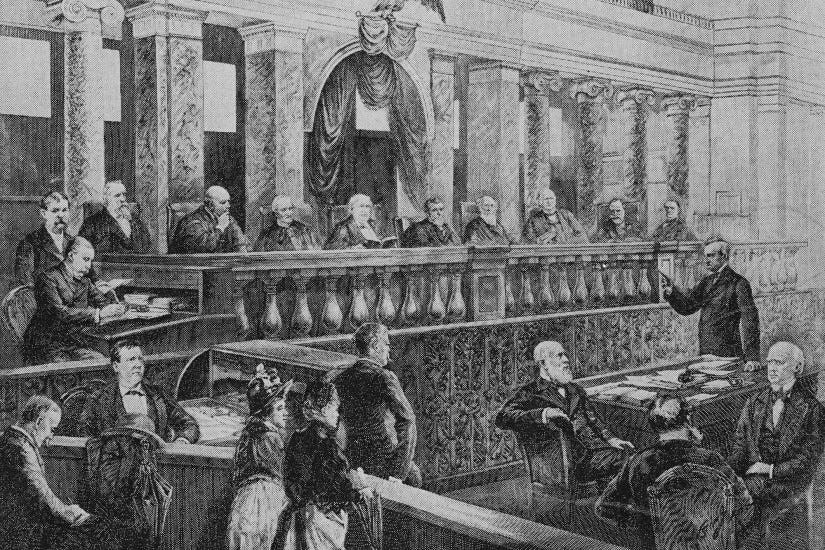

Upon taking office in 1801, Jefferson, with a Democratic-Republican majority in Congress, moved swiftly to dismantle this Federalist framework. The Judiciary Act of 1802, signed into law on April 29, 1802, repealed its predecessor in its entirety. Its most significant provision was the abolition of the sixteen new circuit judgeships, effectively eliminating those courts and their Federalist appointees. The act restored the prior system, where Supreme Court justices resumed their circuit-riding duties, presiding over six circuit courts aligned with the nation’s judicial districts. This reduction streamlined the federal judiciary, aligning it more closely with Jefferson’s preference for a leaner, less intrusive federal government. Additionally, the act reversed the reduction in Supreme Court justices, maintaining the number at six, thus preserving Jefferson’s opportunity to influence the court through future appointments.

The reductions achieved by the Judiciary Act of 1802 were both practical and ideological. Practically, it shrank the federal judiciary’s footprint, eliminating what Jefferson saw as unnecessary and costly positions. The sixteen circuit judgeships, each a lifetime appointment, represented a significant expansion of federal payroll and authority—something Jefferson, a fiscal conservative, opposed. Ideologically, the act struck at the heart of Federalist judicial power. Jefferson distrusted a strong, independent judiciary, viewing it as a potential tool for aristocratic or monarchical tendencies that clashed with his democratic ideals. By abolishing the new courts, he curtailed the Federalists’ ability to use the judiciary as a bulwark against his administration’s policies, such as reducing taxes and shrinking the national government’s scope.

The passage of the Judiciary Act of 1802 was not without controversy. Federalists decried it as an assault on judicial independence, arguing that eliminating judgeships violated the Constitution’s provision for lifetime tenure “during good behavior.” This contention led to legal challenges, most notably Stuart v. Laird (1803), where the Supreme Court upheld the 1802 act, affirming Congress’s authority to alter the structure of lower federal courts. The decision was a blow to Federalist hopes of preserving their judicial gains and underscored the political nature of the judiciary’s evolution. Moreover, the return to circuit-riding placed a physical burden on Supreme Court justices, some of whom, like Samuel Chase, grumbled about the inconvenience, though it reinforced Jefferson’s vision of a judiciary tethered to the practical needs of the nation rather than an elevated, detached institution.

The Judiciary Act of 1802 had lasting implications beyond its immediate reductions. It marked a triumph of Jeffersonian democracy over Federalist elitism, reasserting congressional control over the judiciary’s structure. While it did not eliminate the federal courts entirely - preserving district courts and the Supreme Court - it set a precedent for legislative oversight of judicial organization, a power Congress would wield in future expansions, such as the Judiciary Act of 1869. The act also intensified partisan tensions, foreshadowing battles over judicial appointments that persist in American politics. Jefferson’s success in rolling back the Federalist courts bolstered his administration’s early momentum, though it did little to resolve the deeper ideological divide over the judiciary’s role in a republic.

The Judiciary Act of 1802 stands as a testament to Jefferson’s strategic use of legislative authority to reduce the federal courts established by his predecessors. By abolishing the sixteen circuit judgeships and restoring the circuit-riding system, Jefferson not only shrank the judiciary’s size but also realigned it with his vision of a restrained federal government. This act was a pivotal moment in the early republic, reflecting the interplay of politics and principle in shaping America’s judicial framework.

While Federalists mourned it as a loss of judicial prestige, Jefferson saw it as a victory for democracy - a leaner judiciary better suited to a nation wary of centralized power.

Unless the Senate passes such a bill after passage of cloture, thus cutting off filibuster, no curative legislation similar to the Judiciary Act of 1802 will ever go into effect/law.

Can you visualize Elena Kagen on horseback ?