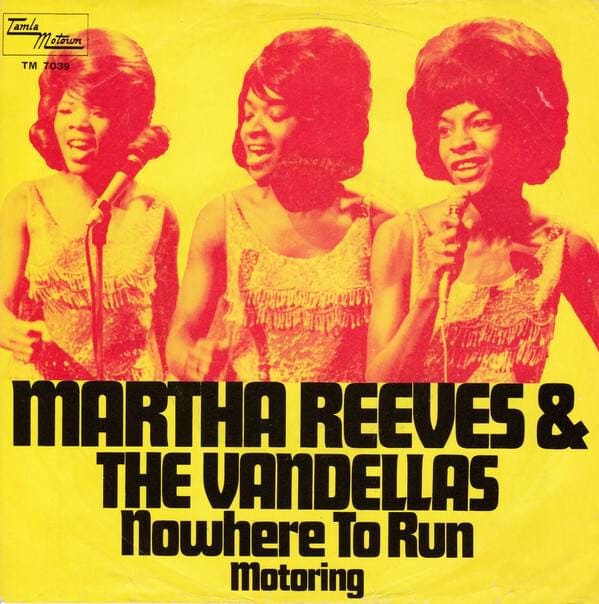

Nowhere to Run

When immigration enforcement is treated like self-defense in a “duty to retreat” state - the illegal alien's presence and preferences matter more than the citizen's right to protection

In American law, self-defense doctrine is not a single rule but a spectrum. It reflects competing intuitions about responsibility, restraint, and the point at which the victim becomes the accused. That same spectrum now quietly governs how much of the political class thinks about immigration enforcement—and the parallels are uncomfortable.

There are three primary legal frameworks for self-defense: Stand Your Ground, the Castle Doctrine, and Duty to Retreat. Each defines how much force a person may use to protect life and property before the state intervenes to punish them for acting.

From strongest to weakest protection of the innocent, Stand Your Ground is the most expansive, Castle Doctrine occupies the middle ground, and Duty to Retreat offers the least protection to the person under threat.

Stand Your Ground laws extend the logic of self-defense beyond the home. If you are lawfully present in a public space and face an imminent threat of death or serious bodily harm, you have no legal obligation to retreat before defending yourself—even with deadly force if necessary. The principle is simple: the law does not require victims to gamble their lives on the hope that an attacker will show mercy.

The Castle Doctrine is more limited but still rooted in moral clarity. Your home is your last redoubt. If an intruder unlawfully enters your dwelling, the law presumes hostile intent. You are not required to flee your own house before defending yourself or your family. Some states extend this principle to vehicles and workplaces.

At the opposite end lies Duty to Retreat. Under this doctrine, if you can safely escape a confrontation in a public place, you must do so before using deadly force. The philosophy sounds humane—violence as an absolute last resort—but it comes at a cost. It transfers risk from the aggressor to the victim, forcing the threatened party to make split-second judgments under stress while prosecutors and juries evaluate those decisions in calm hindsight.

The civil law consequences are where theory becomes grotesque. In wrongful-death and premises-liability suits, families of criminals have successfully argued that homeowners or property owners were responsible for injuries or deaths suffered by intruders. Jurors are asked to weigh biographies instead of actions—“a good boy,” “a quiet student,” “loved by his mother”—as if character references negate criminal conduct. The result is a legal culture that suggests you may survive an attack only to be ruined afterward.

Cases from the late twentieth century made this mindset explicit: burglars who fell through skylights sued homeowners and school districts for unsafe conditions, even though they had no lawful reason to be there in the first place. The message was unmistakable, once the intruder crosses the threshold, responsibility shifts, and the victim must anticipate the criminal’s safety—or pay.

Combine these theories and perspectives with policies of no cash bail, catch and release, demoting the seriousness of crimes, frequent fliers walking free with 20 to 40 arrests and/or convictions (until they final commit a crime that goes public and can no longer be ignored) and you begin to see the same logic now dominates progressive thinking on immigration enforcement.

Minnesota and Illinois have now sued the federal government to stop ICE from enforcing long-standing immigration law. Their argument is not that the law does not exist, nor that Congress repealed it, but that enforcing it creates risk, tension, and moral discomfort. The presence of the intruder becomes the fault of the homeowner for noticing.

This is immigration policy as Duty to Retreat.

The border is breached—often by explicit executive choice—but once the individual is inside the metaphorical fence, the nation is told it must retreat. Enforcement is portrayed as the true violence. Removal is framed as cruelty and resistance to enforcement is moralized as compassion, even when it involves obstructing federal officers or provoking dangerous confrontations.

Just as in duty-to-retreat jurisdictions, the burden of restraint falls entirely on the lawful party. Americans are told to absorb the costs—economic, social, civic, and sometimes physical—because asserting boundaries is considered more offensive than violating them. Like the homeowner sued for a burglar’s injuries, the country is warned that defending itself too firmly will bring civil, political, or moral punishment.

Stand Your Ground does not mean reckless violence, and immigration enforcement does not mean cruelty. Both are assertions that law exists to protect the innocent, not to comfort those who break it.

Any society insisting it must always retreat—always yield, always apologize, always explain—will eventually find that from physical, cultural and civilizational perspectives, there is nowhere left to run.

Perhaps a new concept can be introduced into the self-defense argument. Let's consider a principle of law that we might call, "Duty to Obey", or, perhaps, "Agression Follows Intent". One who is engaged in unlawful activity has voluntarily and willingly placed himself in harm's way, and must suffer the consequences of their choice. A citizen is required to obey the law in order to appeal to its protections. If a citizen breaks the law, they must bear responsibility as the aggressor in any confrontation that may result from that illegal activity. We are not saying that a person loses the rights of the accused as delineated in the Constitution, but in the moment(s) of lawless aggression or disobedience, those rights are subordinated to the person(s) being victimized by those actions or to the legally constituted power(s) of the state, respectively. The victimized citizen would be entitled to use whatever means or methods determined necessary as adjudged by a reasonable person. In other words, a person's actions to protect or defend oneself would be left to their own judgement according to the circumstances, limited only by reasonable attention to the safety of (uninvolved) others and their property. Again, in other words, FAFO. Just a modest proposal for moral clarity.

You have triggered a thought regarding Barak Hussein Obama and the notion of "leading from behind." Montgomery County, MD does not have stand your ground laws; Maryland law requires individuals to retreat, if safely possible, before using deadly force in public. However, the "Castle Doctrine" allows for self-defense without retreating when in one's home. We are planning a move to Florida.